Under Queen Victoria, British archaeologists and adventurers scoured the world for treasures and shipped them back home, where they now take pride of place at London exhibits.

Baghdad, October 24 – Black-market operatives in the archaeological field hoping to score big payouts from looting sites in chaotic areas of the Middle East have voiced repeated frustration that all the really valuable items were already removed by the British more than a hundred years ago, leaving other looters with comparatively nothing.

Baghdad, October 24 – Black-market operatives in the archaeological field hoping to score big payouts from looting sites in chaotic areas of the Middle East have voiced repeated frustration that all the really valuable items were already removed by the British more than a hundred years ago, leaving other looters with comparatively nothing.

Disintegrated central authority and the total collapse of regulatory activity concerning ancient artifacts in countries such as Syria and Iraq over the last ten years has presented myriad opportunities for those who traffic in illicit archaeological treasures to reach sites previously inaccessible. To their chagrin, however, these thieves, smugglers, couriers, traffickers, document forgers, and collectors have had to make do with finds that pale in comparison to the grand collections moved wholesale to the British Museum in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Yusuf, a digger who has looted numerous sites once guarded by Iraqi government agencies but now left untended, lamented the situation in a recent interview. “Elsewhere in the world, a looter can hope to find some truly valuable artifacts,” he noted. “But under Queen Victoria, British archaeologists and adventurers scoured the world for treasures and shipped them back home, where they now take pride of place at London exhibits. That’s just not fair to people such as my brother and I, who have to feed our families with the proceeds of the miserable leftovers.”

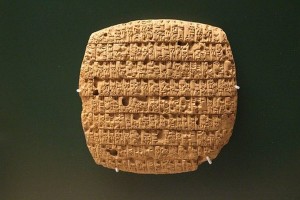

“Look at this jug,” he continued. “It’s a fine Parthian jug, probably second century. Not exactly rare, but still important. I could get maybe a week’s worth of supplies for the family through the right channels. But imagine if the British hadn’t waltzed off with the cuneiform clay tablets aggrandizing the campaigns of Babylonian and Assyrian conquerors. I’d be rich! It’s not right that other thieves got here first, and were backed by the military might of the British Empire.”

Experts noted parallels between the two major looting periods. “When the British were dismantling Pharaonic tombs and reassembling them in London, it was mostly in the context of a disintegrating Ottoman Empire,” explained Phil T. Luker, an antiques assessor with Sotheby’s. “Today, the central authority that no longer exists once resided in Baghdad, as opposed to Istanbul. But the phenomenon is the same, and the circumstances that invite the looting share many attributes.”

“Many activists, academics, and even governments have tried to stem the flow of such artifacts,” he added. “It’s easier now in many ways because the good stuff is all on display or stored in London, so stemming traffic is no big loss to anyone, and the profit motive doesn’t get in the way of caring about ‘cultural integrity.'”

“It’s a different situation compared to, for example, artwork looted by the Nazis from Jews,” he concluded. “There, no one actually cares.”

Please support our work through Patreon.